Data as institutional memory

This is a repost of what I originally posted on Medium in October 2019. I have also moved it here to get around the paywall thing. Let’s be honest if you only have so many free articles and you have the choice between a luminary in their field and a saffron bun loving idiot, well, I don’t blame you.

It all started, as usual, with me running my mouth in the pub.

“You can’t outsource your data models, they’re the manifestation of your institutional memory”.

I thought that was a nice soundbite, I even got some nods. Satisfied with my work I went off to bed without giving it much more thought.

I then reused it in the 8 minutes I had at the Institute for Government’s Data Bites event, firing it off into the audience somewhat haphazardly.

In the pub afterwards, Dan said he liked what I said, and would like me to expand on it in a blog post. So here we are. That’s the trouble with spending time with people you like and respect, when they think you should do something it’s very hard to dismiss their opinion because you like and respect it.

The Wild West (before 2011 when GDS was invented by wizards from the future) 🧙

Before these halcyon days of end to end services, nearly every significant piece of government policy resulted in an application being built, and frequently these applications were outsourced to a big IT supplier.

You’ll find more articulate opinions on that subject than I have with a simple Google search, so for our purposes let’s assume that they were all developed on time, within budget, and bug free.

The fact remains that they were developed in isolation, a by-product of policy and legislation rather than treated as components in a system. What has this meant for our data, and perhaps more importantly, our metadata?

Examples of ill-defined or misaligned data models are legion. One application refers to people as “customers”, another “users”, another “citizens”. Often these models are similar, but they’re never the same.

This is mostly fine, until the policy or legislation changes, and now application one and application two need to talk to each other regularly. Even if both applications were forward thinking enough to provide APIs, the data models are so fundamentally different that transmission isn’t the problem, aligning definition and meaning is.

So now you find yourself in a mire of misaligned, poorly defined, and undocumented data models across a swathe of services, processes, and applications and you would like to realign them? Here’s how I try and tackle this problem (with varying degrees of success I will freely admit).

Fixing the plumbing starts with identifying the leaks

At the risk of sounding like a consultant from one of the big IT firms, you are going to need something to converge on. There’s not really any better term for this than enterprise data models, so enterprise data models it is. Now, hear me out.

What does an enterprise data model look like in the real world? It’s not nearly as technical as you might think it is. Enterprise data models can take many forms, and can include technical components like logical models, vocabularies, or ontologies but that’s not where you should start. Broadly speaking, here’s how I like to tackle the problem.

Clarify the landscape and how people perceive entities

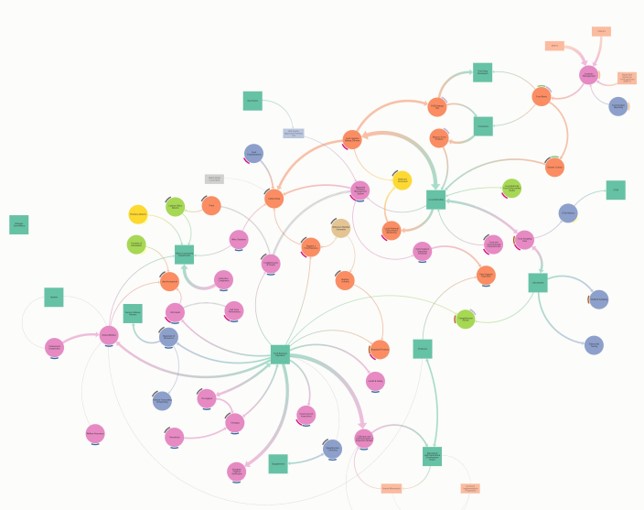

You may already have a good understanding of how your organisation’s services and applications hang together, but judging from the feedback I’ve had when I’ve shown people this diagram, I would suspect you are in the minority.

This first exercise will have benefits beyond improving your data models, so is well worth doing. You need to draw out how all your organisation’s services, applications and processes hang together. Here’s a picture of a map1 I’ve created here at the FSA;

A screenshot of the FSA data ecosystem map. This is roughly how our services, applications and processes move data around between each other and our various users.2

Examine the reality of those entities

If you now understand how things hang together, what do you do with that information?

There’s no escaping it, you’re going to have to go find the technical documentation. Chances are that documentation is patchy at best and outright missing at worst. Which is why in government you need a two-pronged approach which includes reviewing policy and legislation documents as well. Entities are often described quite well in these records, even if they’re written in legalese. Some other things to consider;

What are the entities and how are they defined?

Make a list and show the relationship between entities which you think are synonymous and those which are just similar. Has their language changed over time?

Did we start with “establishment” which added “approved establishments” and “registered establishments” because of policy or legislative changes or were some applications developed in ignorance of the difference because it didn’t matter at the time?

Do they have properties in the application that are not obvious to users?

Data models are frequently more sophisticated than the application presents and often have properties users never see but could be useful.

Have users re-purposed parts of an application to extend the data model in some way?

A classic example of this is business processes structuring free text fields so that they have additional meaning through codes or patterns. You will find this frequently in case notes fields in operational systems. Uncovering these usages and the reasons they exist will often give you loads of good insider information.

Are there any lists or controlled vocabularies that you can re-use?

Finding these is manna from heaven.

Now you should better understand both the reality and the perception of your data entities, where they align and where they don’t what do you do with that information?

Start to align entities

Start with one, a small one if you like but get it written down. Describe the entity clearly, use the language of the organisation not the language of technology.

Then test it with subject matter experts, ask them to probe the edges to find out where the model fails. There will always be edge cases, but your enterprise models must be robust enough to communicate the key properties of entities that exist across systems and implementations.

Enterprise data models are about convergence, not conformance. It’s very easy to convince senior leaders that this is all a mess and I have a way out of it, please give me a suitable stick with which to beat everyone else into submission. Down that road lies failure, as institutional memory acts more like a decentralised guerrilla network than a central repository. It is very resistant to change if it thinks you’re wrong.

My preferred approach is to catch applications and services as they inevitably appear in the pipeline for improvement work. If users want changes to an application because it will improve their day to day experience then use that as your opportunity to clean the data models too to improve the experience of those that will need to use or improve it in the future.

It might mean changing some field names here, rebuilding a database, or just improving documentation. You’re trying to undo a couple of decades of entropy, and you’ll want to do that incrementally.

Why do it this way, why do it at all?

Here at the FSA, we’re small in comparison to other government departments. We must be sure that improving a service or developing a new one is the right thing to do at the right time, and that includes devoting time to designing, improving and documenting data models. Everything has a cost.

Development is expensive and the less time you need to spend figuring out what the correct data model for a service is, the more time you can spend improving services. Having robust data models which can be extended if needed is a much better place to start from than building from scratch every time.

The more services that share data models and entity definition, the less time your data science and analytical teams need to spend cleaning and aligning data.

Good enterprise data models help your organisation more easily adapt to change. Could your organisation cope with the loss of institutional knowledge caused by a lottery syndicate comprised of an entire policy team winning the lottery and leaving? If your organisation was split, merged, or absorbed by a larger one would the institutional knowledge built up over many years survive?

For too long, organisations have thought about data as the by-product of policy, but now we need to think of data (and metadata) as an integral part of those policies.

Describing entities accurately allows experts to focus on outcomes rather than arguing about definitions and rules. This is work worth doing, but it can be a slog because we’ve let it go for so long.

We need to do this, because we can’t go on fixing the plumbing forever. We need to think about how we design data to be an asset fit for the 21st century.

I dread to think the kinds of problems that await us in the world of algorithmic and A.I. services if we don’t do this work, because like it or not, those things are coming, and they are data hungry, let’s try and give them the data equivalent of a balanced diet.

1: It’s not actually a map, as Simon Wardley explains here, but everyone keeps calling it a map because that’s how brains work I guess?

2: Yes, I will do another blog on how I put this together and what I learned but that will be sometime in the future. I don’t have a track record as a prolific blogger let’s be honest.